In 2009, I had two live event experiences where I felt “out of place.”

In 2009, I had two live event experiences where I felt “out of place.”

The first was in April, when I was in “the pit” (at the front of the floor section) for a Bruce Springsteen concert. My brother was there as a big fan who had never seen the Boss in concert before, whereas I was there because I was travelling with my brother, and because I enjoy Bruce Springsteen’s music in a purely casual fashion. So when the people around us started discussing how they were there at the Darkness Tour in ‘78, and how this was their ninth show, and how they had already seen him twice on this tour alone, I felt more than a little bit of an outcast (loved the show, by the way).

Then, in the fall, I went to a WWE House Show here in Halifax, where I felt out of place in a different way. While I have never been a big Bruce Springsteen fan, I used to be a big pro wrestling fan in my childhood (and, okay, my teenage years as well), so the kid in front of me elated to be able to slap the hands of the wrestlers going by in the aisle and the douchebag who yells and insults the wrestlers and thinks its funny were people that I used to be, or used to relate with on online message boards (oh, those were the days). And while Springsteen made me seem out of place, there was something about returning to the world of professional wrestling that felt more profound: I used to be part of this world, and even if I no longer relate to either of those roles (I had a lot of fun taking photos, though) personally I understand them enough to continue to find wrestling an intriguing element of the cultural landscape even if I could no longer find a place in that universe.

And so I’ve watched with only moderate interest as the WWE brand has expanded into providing something closer to “entertainment” than “sports entertainment” with their recent (brilliant) decision to bring in guest hosts to their weekly Monday Night Raw episodes in order to boost revenue (the spots are effectively being sold) and exposure (both in terms of bringing in fans of the hosts and in terms of media coverage of more high-profile guests). I haven’t written about it largely because there’s no real nuance to it, as they readily admit that it’s a business decision first and foremost, and because the creative results haven’t been enough to convince me that the actual WWE product (from which I’ve been disconnected for the better part of the past decade) is worth diving back into to catch Jeremy Piven or (later this month) James Roday and Dule Hill from Psych stepping into the ring.

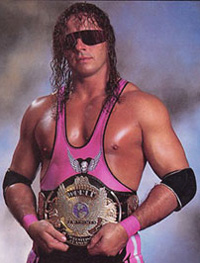

It’s no coincidence that, with a healthy dose of nostalgia guiding the way, my first foray into the world of wrestling in the context of television criticism comes when the new “Guest Host” format engages with my childhood wrestling fandom, as Bret “The Hitman” Hart (the obvious choice for my favourite wrestler growing up considering I was Canadian) returns to the WWE after a decade-long absence, and after an infamous Montreal screwjob that was a rare “storyline” with real world implications. And this week’s episode of Raw is a unique glimpse into how the injection of “real” drama heightens the fictional world of professional wrestling, and how nostalgic remembrance and wrestling’s traditional Good vs. Evil storytelling converge in order to turn twelve years of bad blood into a narrative that can capture old and new fans alike.

Yes, seriously.

What’s unique about wrestling is that an individual like Bret “The Hitman” Hart occupies both specific and non-specific positions depending on who is watching or paying attention to wrestling. For those of us who were watching wrestling during his prime years in the WWE (then the WWF, of course), you remember him for his time in the Hart Foundation, and his cinderella World Title victory in Calgary (a rare occurrence where a title changed hands off of live television), or the circumstances surrounding his exit. And yet, for young wrestling fans who barely know who Steve Austin is yet alone who Bret Hart is, he is nothing but a guy fighting against the man (in this case WWE Chairman Vince McMahon), the requisite “face” to McMahon’s “heel.”

“Pro Wrestling” storylines (its form of narrative) all operate on those two levels, playing into both long-standing conflicts (in this case a decade-long feud that has taken place largely outside of the ring) and the traditional battle between good and evil, between the individual and the corporation, etc. And so Bret “The Hitman” Hart can be someone different to two different audiences, and his appearance can offer both a portal into wrestling fans like me (who, I will not lie, complained of a dusty room when the Montreal Screwjob went down) and the kids who watch wrestling because it has heroes beating up people who deserve to be beat up. And magically, through the power of a well-cut promo and a video package or two, there’s every chance that the two groups could converge: the nostalgic fans are sucked back into the current plays on good vs. evil, and the young kids start to better understand who Bret Hart is and why his appearance is such a big deal for lapsed wrestling fans from my generation.

The initial confrontation between Hart and the man who helped facilitate the screwjob (Shawn Michaels) is indicative of the complexity that they’re playing with here. In narrative terms, this is a moment twelve years in the making, and the sheer longevity of its story is almost overwhelming: the crowd doesn’t know whether to root for the two to “bury the hatchet” or whether they want Shawn to turn into a villain and fit more comfortably into definitions of good and evil (that was my hope, personally). It doesn’t help that Shawn is someone who fans love presently despite his association with this event. The scene (let’s remind ourselves that this was scripted) gives a sense of closure while reminding us that things are too complicated to be resolved without the presence of Vince McMahon, and a reminder that this resolution is far more electric than two (relatively) old guys in a wrestling ring with microphones has any business being. There’s a lot of history between the two men (as Shawn evokes with the Iron Man match at Wrestlemania XII), but that history (stretching back to their time as tag team wrestlers in their early years in the company, including a feud between the Hart Foundation, the Rockers (Michaels and Marty Jannetty) and Demolition) has been so defined by this single moment (both inside and outside of the ring) that a promo like this has, perhaps, never happened before (the closest comparison perhaps being the company attempts to turn the real-life feud with WCW into a storyline after buying the company, which was ultimately a flop).

What makes all of it work is that they very clearly know what the audience is expecting, and they did everything in their power to build to that moment. There’s small beats where astute viewers will notice the opportunity for Michaels to break out his “Sweet Chin Music” and turn on Bret, and every pause in the conversation is less a delay and more an opportunity for someone to deliver a sucker punch. It gives the promos a feeling, for those of us who understand the history at play, that they’re actually not scripted, that there’s every chance that Bret or Shawn could go “off book” similar to the Screwjob in question. Bret isn’t the most gifted actor (he never was), but his straightforward approach is perfect for making this seem far more real than it actually is, and the fact that this was actually at one point real – that these guys actually hated each other’s guts – only adds to its effectiveness at playing into our nostalgia.

Watching the rest of the show (I suffer for my art sometimes), no other promo could possibly compare: while my Canadianness meant I was excited to see Hart and Chris Jericho together, Hart only appeared in three sequences, and in between the difference was clear. Other promos all felt even more false than usual, so lacking in any sort of deeper meaning beyond feuds written and constructed behind the scenes. The collective weight of twelve years of bad blood made any other feud seem fake to the point of parody, which isn’t entirely abnormal for the WWE but rarely feels as clear as it did on this night. As a result, when Vince McMahon came to the ring to close out the show, the world was going to finally get the confrontation that they had been waiting twelve years to see.

Except for the fact that, by the time you got to that scene and by the time you realized the degree to which Vince McMahon’s on-screen persona has never said an honest word (and Vince has never been able to sell anything beyond slimeball), any sense of reality was all but washed away. While it was still powerful to have the two men in the ring together, we went into that confrontation with foreknowledge that Hart has signed a multi-month contract with the company, so the uncertainty surrounding Michaels (who is a far more capable actor, and who kept us guessing in his confrontation with Bret) was completely absent here. So when Vince and Bret reached a resolution similar to Michaels’, you knew that it wasn’t going to end that way, and sure enough a kick to the groin sells what Vince McMahon sold twelve years ago: he is this universe’s evil mastermind, and Bret Hart is just another wrestler who stood in the way of his plans. It essentially reboots the feud, creating a scenario where Bret will be able to seek out the vengeance that he wasn’t able to get “in the ring” twelve years ago, which officially transitions the storyline from real life to the fictional world of sports entertainment – the real feud, we realize in that final moment even if we should have known it from the beginning, ended long before the cameras started rolling. We might have been left wanting more, but that’s sort of the point: they want us to return next week, and the week after, in the hope that we’ll finally get the justice we crave.

Wrestling is never going to feel real (that ship sailed a long time ago), but there are times when long term feuds or real life circumstances give the show’s storylines a sense of an actual narrative, with history and personalities colliding in a way which creates legitimate suspense not just on who is going to win, but what is going to happen. When Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels stood together in that ring, the company evoked the one moment in its past which was unquestionably real, and tonight they leveraged that event to deliver some captivating television for us nostalgic folks and to start a new storyline that can bring that story to a new audience who has yet to become acquainted with the excellence of execution.

And that’s pretty impressive, even if they’ll never be able to duplicate it again.

Cultural Observations- Rival TNA offered their own show (featuring a literal parade of nostalgia headlined by Hulk Hogan) in the same timeslot in an attempt to recreated the epic Monday Night Wars of old, but they have no history to go with it: it’s just pure nostalgia, which is fine as a one-time shot but does nothing for long term development.

- One bit of strange development: last week, Shawn Michaels suggested that Vince should allow Bret to appear because “something good will come of it.” The insinuation there was that Shawn would be part of something sinister planned for Bret, so I’ll be curious to see if that was a narrative thread designed to throw us off the scent in the first sequence or a sign that Shawn’s role might become more complicated moving forward. And yes, I expect narrative continuity from professional wrestling: this is what criticism has done to me.

- Apparently, writing about wrestling is like riding a bike, so I could go on. I’ll stop here, though, and open up the comments for anyone willing to admit they tuned in to see the return of the Hitman.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий